Python Strings - Common Data Structures

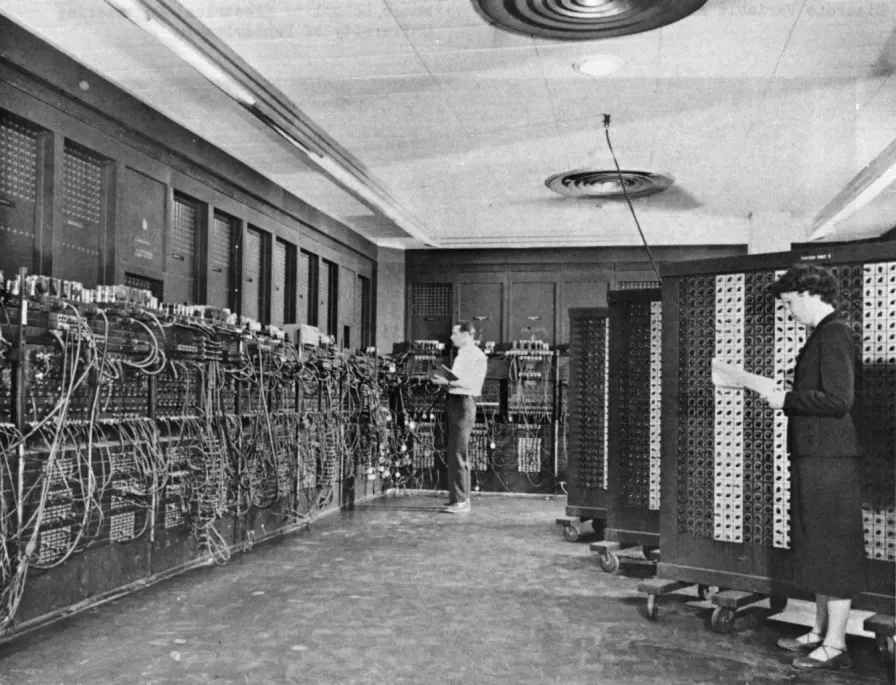

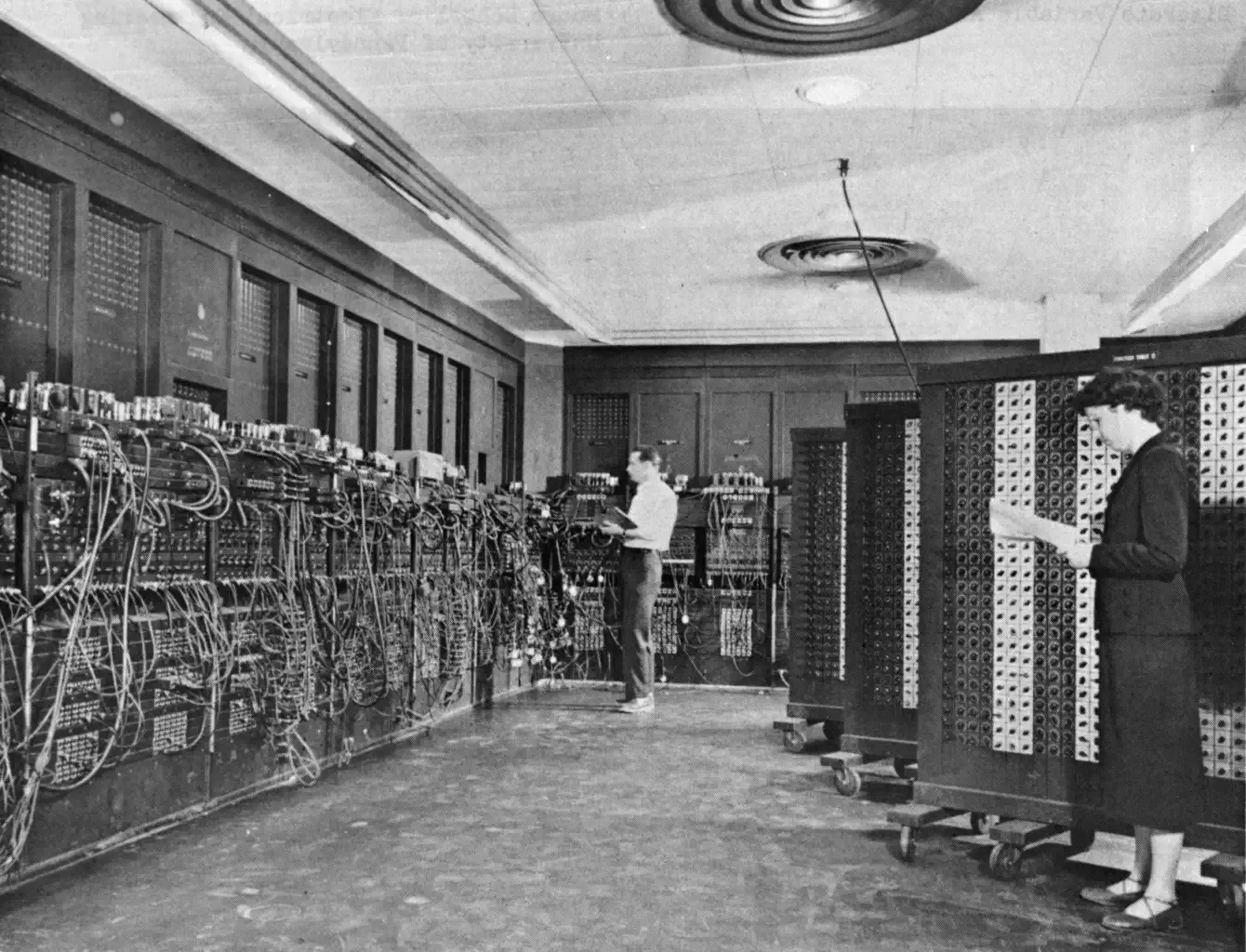

The Second World War prompted the birth of modern electronic computers. The world’s first general-purpose electronic computer was called ENIAC (Electronic Numerical Integrator and Computer), born at the University of Pennsylvania in the United States. It occupied 167 square meters, weighed about 27 tons, and could perform approximately 5,000 floating-point operations per second, as shown in the image below. After ENIAC was born, it was applied to missile trajectory calculations, and numerical computation remains one of the most important functions of modern electronic computers.

As time has passed, although numerical operations are still the most important part of a computer’s daily work, today’s computers also need to process large amounts of information that exists in text form. If we want to manipulate this text information through Python programs, we must first understand the string data type and its related operations and methods.

String Definition

A string is a finite sequence composed of zero or more characters, generally denoted as:

$$ s = a_1a_2 \cdots a_n ,,,, (0 \le n \le \infty) $$

In Python programs, we can represent a string by enclosing single or multiple characters in single quotes or double quotes. Characters in a string can be special symbols, English letters, Chinese characters, Japanese hiragana or katakana, Greek letters, Emoji characters (such as: 💩, 🐷, 🀄️), etc.

s1 = 'hello, world!'

s2 = "你好,世界!❤️"

s3 = '''hello,

wonderful

world!'''

print(s1)

print(s2)

print(s3)Escape Characters

We can use \ (backslash) in strings to represent escape sequences, meaning that the character after \ no longer has its original meaning. For example: \n doesn’t represent the characters \ and n, but represents a newline; \t doesn’t represent the characters \ and t, but represents a tab character. So if the string itself contains special characters like ', ", or \, they must be escaped using \. For example, to output a string with single quotes or backslashes, you need to use the following method.

s1 = '\'hello, world!\''

s2 = '\\hello, world!\\'

print(s1)

print(s2)Raw Strings

Python has a type of string that starts with r or R, called a raw string, meaning that each character in the string has its literal meaning, with no escape characters. For example, in the string 'hello\n', \n represents a newline; but in r'hello\n', \n no longer represents a newline, it’s just the characters \ and n. You can run the following code to see what it outputs.

s1 = '\it \is \time \to \read \now'

s2 = r'\it \is \time \to \read \now'

print(s1)

print(s2)Note: In the variable

s1above,\t,\r, and\nare all escape characters.\tis a tab character,\nis a newline character, and\ris a carriage return character that returns the output to the beginning of the line. Compare the output of the two

Special Character Representation

Python also allows you to follow \ with an octal or hexadecimal number to represent a character. For example, \141 and \x61 both represent the lowercase letter a, the former is octal notation, the latter is hexadecimal notation. Another way to represent characters is to follow \u with a Unicode character code, for example \u9a86\u660a represents the Chinese characters “骆昊”. Run the following code to see what it outputs.

s1 = '\141\142\143\x61\x62\x63'

s2 = '\u9a86\u660a'

print(s1)

print(s2)String Operations

Python provides very rich operators for string types, many of which work similarly to list type operators. For example, we can use the + operator to concatenate strings, use the * operator to repeat string content, use in and not in to determine if a string contains another string, and we can also use [] and [:] operators to extract certain characters or substrings from a string.

Concatenation and Repetition

The following example demonstrates using the + and * operators to implement string concatenation and repetition operations.

s1 = 'hello' + ', ' + 'world'

print(s1) # hello, world

s2 = '!' * 3

print(s2) # !!!

s1 += s2

print(s1) # hello, world!!!

s1 *= 2

print(s1) # hello, world!!!hello, world!!!Using * to repeat strings is a very interesting operator. In many programming languages, to represent a string with 10 as, you can only write 'aaaaaaaaaa', but in Python, you can write 'a' * 10. You might think that writing 'aaaaaaaaaa' isn’t inconvenient, but think about what would happen if the character a needed to be repeated 100 or 1000 times?

Comparison Operations

For two string type variables, you can directly use comparison operators to determine string equality or compare sizes. It should be noted that because strings also exist in binary form in computer memory, string size comparison compares the size of each character’s corresponding encoding. For example, the encoding of A is 65, while the encoding of a is 97, so the result of 'A' < 'a' is equivalent to the result of 65 < 97, which is obviously True; and for 'boy' < 'bad', because the first character is 'b' in both cases and can’t be compared, the second character is actually compared, and obviously 'o' < 'a' is False, so 'boy' < 'bad' is False. If you’re not sure what the encoding of two characters is, you can use the ord function to get it, as we mentioned before. For example, ord('A') is 65, and ord('昊') is 26122. The following code demonstrates string comparison operations, please look carefully.

s1 = 'a whole new world'

s2 = 'hello world'

print(s1 == s2) # False

print(s1 < s2) # True

print(s1 == 'hello world') # False

print(s2 == 'hello world') # True

print(s2 != 'Hello world') # True

s3 = '骆昊'

print(ord('骆')) # 39558

print(ord('昊')) # 26122

s4 = '王大锤'

print(ord('王')) # 29579

print(ord('大')) # 22823

print(ord('锤')) # 38180

print(s3 >= s4) # True

print(s3 != s4) # TrueMembership Operations

In Python, you can use in and not in to determine if a string contains another character or string. Like list types, in and not in are called membership operators and produce boolean values True or False, as shown in the following code.

s1 = 'hello, world'

s2 = 'goodbye, world'

print('wo' in s1) # True

print('wo' not in s2) # False

print(s2 in s1) # FalseGetting String Length

Getting the string length is the same as getting the number of list elements, using the built-in function len, as shown in the following code.

s = 'hello, world'

print(len(s)) # 12

print(len('goodbye, world')) # 14Indexing and Slicing

String indexing and slicing operations are almost no different from lists and tuples, because strings are also ordered sequences and can access their elements through positive or negative integer indices. But one thing to note is that strings are immutable types, so you cannot modify characters in a string through index operations.

s = 'abc123456'

n = len(s)

print(s[0], s[-n]) # a a

print(s[n-1], s[-1]) # 6 6

print(s[2], s[-7]) # c c

print(s[5], s[-4]) # 3 3

print(s[2:5]) # c12

print(s[-7:-4]) # c12

print(s[2:]) # c123456

print(s[:2]) # ab

print(s[::2]) # ac246

print(s[::-1]) # 654321cbaIt needs to be reminded again that when performing index operations, if the index is out of bounds, it will raise an IndexError exception with the error message: string index out of range.

Character Traversal

If you want to traverse each character in a string, you can use a for-in loop in the following two ways.

Method 1:

s = 'hello'

for i in range(len(s)):

print(s[i])Method 2:

s = 'hello'

for elem in s:

print(elem)String Methods

In Python, we can operate on and process strings through methods that come with the string type. Assuming we have a string named foo and the string has a method named bar, the syntax for using string methods is: foo.bar(), which is a syntax for calling object methods through object references, the same as the syntax for using list methods we saw before.

Case-Related Operations

The following code demonstrates methods related to string case conversion.

s1 = 'hello, world!'

# Capitalize first letter of string

print(s1.capitalize()) # Hello, world!

# Capitalize first letter of each word in string

print(s1.title()) # Hello, World!

# Convert string to uppercase

print(s1.upper()) # HELLO, WORLD!

s2 = 'GOODBYE'

# Convert string to lowercase

print(s2.lower()) # goodbye

# Check values of s1 and s2

print(s1) # hello, world

print(s2) # GOODBYENote: Since strings are immutable types, using string methods to operate on strings produces new strings, but the value of the original variable does not change. So in the code above, when we finally check the values of the two variables

s1ands2, the values ofs1ands2have not changed.

Search Operations

If you want to search forward in a string for another string, you can use the string’s find or index method. When using the find and index methods, you can also specify the search range through method parameters, meaning the search doesn’t have to start from position index 0.

s = 'hello, world!'

print(s.find('or')) # 8

print(s.find('or', 9)) # -1

print(s.find('of')) # -1

print(s.index('or')) # 8

print(s.index('or', 9)) # ValueError: substring not foundNote: The

findmethod returns-1if it can’t find the specified string, while theindexmethod raises aValueErrorerror if it can’t find the specified string.

The find and index methods also have reverse search versions (searching from back to front), which are rfind and rindex, as shown in the following code.

s = 'hello world!'

print(s.find('o')) # 4

print(s.rfind('o')) # 7

print(s.rindex('o')) # 7

# print(s.rindex('o', 8)) # ValueError: substring not foundProperty Checking

You can use the string’s startswith and endswith methods to determine if a string starts or ends with a certain string; you can also use methods starting with is to check string characteristics. These methods all return boolean values, as shown in the following code.

s1 = 'hello, world!'

print(s1.startswith('He')) # False

print(s1.startswith('hel')) # True

print(s1.endswith('!')) # True

s2 = 'abc123456'

print(s2.isdigit()) # False

print(s2.isalpha()) # False

print(s2.isalnum()) # TrueNote: The

isdigitabove is used to determine if a string is composed entirely of digits,isalphais used to determine if a string is composed entirely of letters, where letters refer to Unicode characters but do not include Emoji characters, andisalnumis used to determine if a string is composed of letters and digits.

Formatting

In Python, string types can be centered, left-aligned, and right-aligned using the center, ljust, and rjust methods. If you want to pad zeros on the left side of a string, you can also use the zfill method.

s = 'hello, world'

print(s.center(20, '*')) # ****hello, world****

print(s.rjust(20)) # hello, world

print(s.ljust(20, '~')) # hello, world~~~~~~~~

print('33'.zfill(5)) # 00033

print('-33'.zfill(5)) # -0033We mentioned before that when outputting strings with the print function, you can format strings in the following way.

a = 321

b = 123

print('%d * %d = %d' % (a, b, a * b))Of course, we can also use the string’s format method to complete string formatting, as shown in the following code.

a = 321

b = 123

print('{0} * {1} = {2}'.format(a, b, a * b))Starting from Python 3.6, there is an even more concise way to write formatted strings, which is to add f before the string to format it. In this type of string starting with f, {variable_name} is a placeholder that will be replaced by the corresponding value of the variable, as shown in the following code.

a = 321

b = 123

print(f'{a} * {b} = {a * b}')If you need to further control the form of variable values in formatting syntax, you can refer to the following table for string formatting operations.

| Variable Value | Placeholder | Formatted Result | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

3.1415926 | {:.2f} | '3.14' | Keep two decimal places |

3.1415926 | {:+.2f} | '+3.14' | Keep two decimal places with sign |

-1 | {:+.2f} | '-1.00' | Keep two decimal places with sign |

3.1415926 | {:.0f} | '3' | No decimal places |

123 | {:0>10d} | '0000000123' | Pad left with 0 to 10 digits |

123 | {:x<10d} | '123xxxxxxx' | Pad right with x to 10 digits |

123 | {:>10d} | ' 123' | Pad left with spaces to 10 digits |

123 | {:<10d} | '123 ' | Pad right with spaces to 10 digits |

123456789 | {:,} | '123,456,789' | Comma-separated format |

0.123 | {:.2%} | '12.30%' | Percentage format |

123456789 | {:.2e} | '1.23e+08' | Scientific notation format |

Trimming Operations

The string’s strip method can help us get a string with specified characters trimmed from both ends of the original string, with the default being to trim whitespace characters. This method is very practical and can be used to remove leading and trailing spaces that users may accidentally enter. The strip method also has lstrip and rstrip versions, and I believe you can guess from the names what these two methods do.

s1 = ' jackfrued@126.com '

print(s1.strip()) # jackfrued@126.com

s2 = '~你好,世界~'

print(s2.lstrip('~')) # 你好,世界~

print(s2.rstrip('~')) # ~你好,世界Replacement Operations

If you want to replace specified content in a string with new content, you can use the replace method, as shown in the following code. The first parameter of the replace method is the content to be replaced, the second parameter is the replacement content, and you can also specify the number of replacements through the third parameter.

s = 'hello, good world'

print(s.replace('o', '@')) # hell@, g@@d w@rld

print(s.replace('o', '@', 1)) # hell@, good worldSplitting and Joining

You can use the string’s split method to split a string into multiple strings (placed in a list), and you can also use the string’s join method to connect multiple strings in a list into one string, as shown in the following code.

s = 'I love you'

words = s.split()

print(words) # ['I', 'love', 'you']

print('~'.join(words)) # I~love~youIt should be noted that the split method uses spaces for splitting by default, but we can also specify other characters to split the string, and we can also specify the maximum number of splits to control the splitting effect, as shown in the following code.

s = 'I#love#you#so#much'

words = s.split('#')

print(words) # ['I', 'love', 'you', 'so', 'much']

words = s.split('#', 2)

print(words) # ['I', 'love', 'you#so#much']Encoding and Decoding

In addition to the string str type, Python also has a byte string type (bytes) that represents binary data. A byte string is a finite sequence composed of zero or more bytes. Through the string’s encode method, we can encode a string into a byte string according to a certain encoding method, and we can also use the byte string’s decode method to decode a byte string into a string, as shown in the following code.

a = '骆昊'

b = a.encode('utf-8')

c = a.encode('gbk')

print(b) # b'\xe9\xaa\x86\xe6\x98\x8a'

print(c) # b'\xc2\xe6\xea\xbb'

print(b.decode('utf-8')) # 骆昊

print(c.decode('gbk')) # 骆昊Note that if the encoding and decoding methods are inconsistent, it will lead to garbled text (unable to reproduce the original content) or raise a UnicodeDecodeError error, causing the program to crash.

Other Methods

For string types, another common operation is pattern matching, which checks whether a string satisfies a specific pattern. For example, a website’s check of usernames and emails in user registration information is pattern matching. The tool for implementing pattern matching is called regular expressions, and Python provides support for regular expressions through the re module in the standard library. We will explain this knowledge point in subsequent courses.

Summary

Knowing how to represent and manipulate strings is very important for programmers because we often need to process text information. In Python, strings can be manipulated using concatenation, indexing, slicing and other operators, as well as using the very rich methods provided by the string type.