Introduction to Object-Oriented Programming in Python

Object-oriented programming is a very popular programming paradigm. A programming paradigm is a methodology for program design, simply put, it’s the programmer’s cognition and understanding of programs and their way of writing code.

In previous lessons, we said that “a program is a collection of instructions”. When running a program, the statements in the program become one or more instructions, which are then executed by the CPU (Central Processing Unit). To simplify program design, we also discussed functions, placing relatively independent and frequently reused code into functions, and calling the functions when we need to use this code. If a function’s functionality is too complex and bloated, we can further decompose the function into multiple sub-functions to reduce system complexity.

I wonder if everyone has noticed that programming is actually about the person writing the program controlling the machine to complete tasks through code according to the computer’s working method. However, the computer’s working method is different from human normal thinking patterns. If programming must abandon human normal thinking methods to cater to computers, much of the fun of programming is lost. Here, I want to say that it’s not that we can’t write code according to the computer’s working method, but when we need to develop a complex system, this approach makes the code too complex, making development and maintenance work extremely difficult.

As software complexity increases, writing correct and reliable code becomes an extremely arduous task. This is why many people firmly believe that “software development is the most complex activity among all human activities to transform the world”. How to describe complex systems and solve complex problems with programs has become a problem that all programmers must think about and face. Smalltalk, born in the 1970s, gave software developers hope because it introduced a new programming paradigm called object-oriented programming. In the world of object-oriented programming, data in a program and functions that operate on data are a logical whole, which we call an object. Objects can receive messages, and the method to solve problems is to create objects and send various messages to objects. Through message passing, multiple objects in a program can work together, thus constructing complex systems and solving real-world problems. Of course, the prototype of object-oriented programming can be traced back to the earlier Simula language, but this is not the focus of our discussion.

Note: Many high-level programming languages we use today support object-oriented programming, but object-oriented programming is not the “silver bullet” for solving all problems in software development, or rather, there is currently no so-called “silver bullet” in the software development industry. Regarding this issue, you can refer to the paper “No Silver Bullet: Essence and Accidents of Software Engineering” published by Frederick Brooks, the father of the IBM360 system, or the classic software engineering book “The Mythical Man-Month”.

Classes and Objects

If I had to summarize object-oriented programming in one sentence, I think the following statement is quite incisive and accurate.

Object-oriented programming: Combine a set of data and methods for processing data into objects, categorize objects with the same behavior into classes, hide internal details of objects through encapsulation, implement class specialization and generalization through inheritance, and implement dynamic dispatch based on object types through polymorphism.

This sentence may not be so easy for beginners to understand, but I can first circle a few keywords for everyone: object, class, encapsulation, inheritance, polymorphism.

Let’s first talk about the two words class and object. In object-oriented programming, a class is an abstract concept, and an object is a concrete concept. We extract the common characteristics of the same type of objects to form a class. For example, we often talk about humanity, which is an abstract concept, and each of us is a real existence under the abstract concept of humanity, which is an object. In short, a class is a blueprint and template for objects, and an object is an instance of a class, an entity that can receive messages.

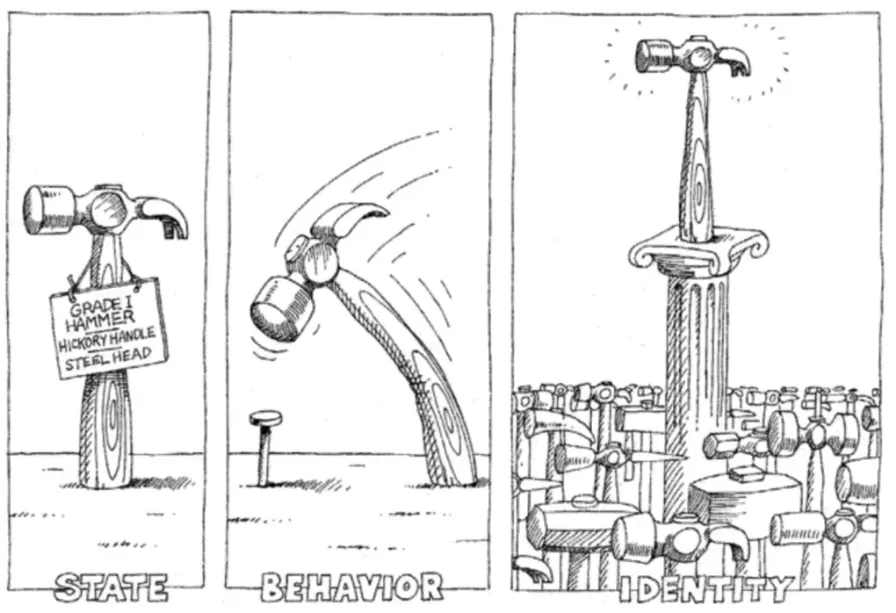

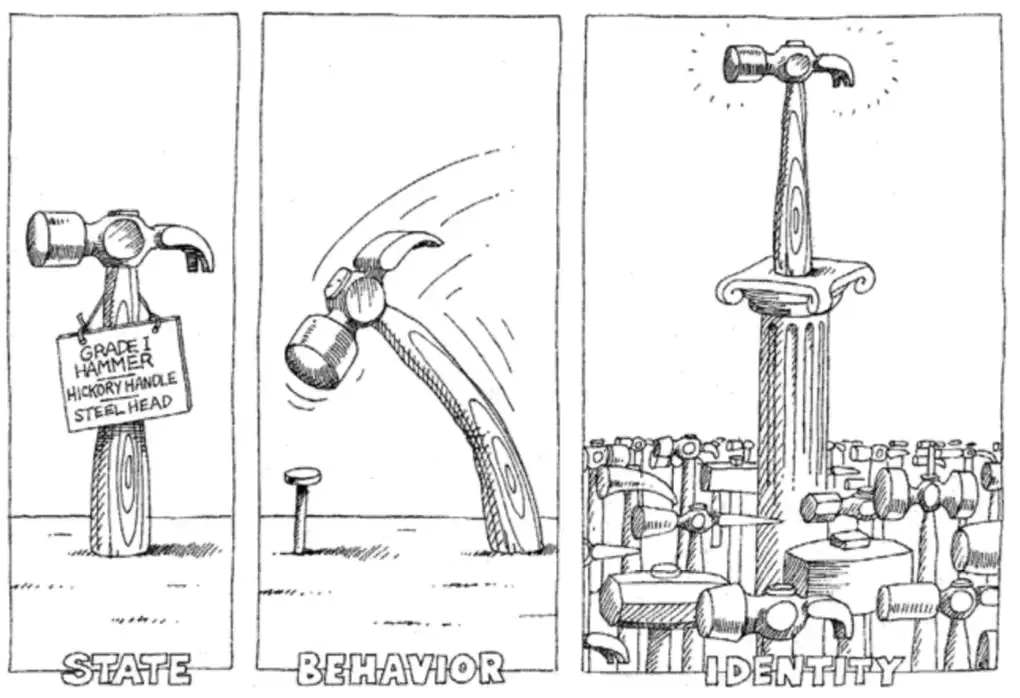

In the world of object-oriented programming, everything is an object, objects have attributes and behaviors, each object is unique, and objects must belong to a certain class. An object’s attributes are the object’s static characteristics, and an object’s behaviors are the object’s dynamic characteristics. According to the above statement, if we extract the attributes and behaviors of objects with common characteristics, we can define a class.

Defining Classes

In Python, we can use the class keyword plus the class name to define a class. Through indentation, we can determine the class’s code block, just like defining functions. In the class’s code block, we need to write some functions. We said that a class is an abstract concept, so these functions are our extraction of the common dynamic characteristics of a type of object. Functions written inside a class are usually called methods. Methods are the behaviors of objects, that is, the messages objects can receive. The first parameter of a method is usually self, which represents the object itself that receives this message.

class Student:

def study(self, course_name):

print(f'Student is studying {course_name}.')

def play(self):

print(f'Student is playing games.')Creating and Using Objects

After we define a class, we can use constructor syntax to create objects, as shown in the code below.

stu1 = Student()

stu2 = Student()

print(stu1) # <__main__.Student object at 0x10ad5ac50>

print(stu2) # <__main__.Student object at 0x10ad5acd0>

print(hex(id(stu1)), hex(id(stu2))) # 0x10ad5ac50 0x10ad5acd0Following the class name with parentheses is the so-called constructor syntax. The code above creates two student objects, one assigned to variable stu1 and one assigned to variable stu2. When we print the stu1 and stu2 variables with the print function, we see the output of the object’s address in memory (in hexadecimal form), which is the same value we get when we use the id function to view the object’s identity. Now we can tell everyone that the variables we define actually save a logical address (position) of an object in memory. Through this logical address, we can find this object in memory. So an assignment statement like stu3 = stu2 doesn’t create a new object, it just saves the address of an existing object with a new variable.

Next, let’s try sending messages to objects, that is, calling object methods. In the Student class just now, we defined two methods, study and play. The first parameter self of both methods represents the student object receiving the message, and the second parameter of the study method is the name of the course being studied. In Python, there are two ways to send messages to objects. Please look at the code below.

# Call method through "Class.method"

# First parameter is the object receiving the message

# Second parameter is the course name being studied

Student.study(stu1, 'Python Programming') # Student is studying Python Programming.

# Call method through "object.method"

# The object before the dot is the object receiving the message

# Only need to pass the second parameter, the course name

stu1.study('Python Programming') # Student is studying Python Programming.

Student.play(stu2) # Student is playing games.

stu2.play() # Student is playing games.Initialization Method

Everyone may have already noticed that the student objects we just created only have behaviors but no attributes. If we want to define attributes for student objects, we can modify the Student class by adding a method named __init__. When we call the Student class’s constructor to create objects, first the memory space needed to save the student object is obtained in memory, and then the __init__ method is automatically executed to complete the initialization operation of the memory, that is, putting data into the memory space. So we can add attributes to student objects and complete the operation of assigning initial values to attributes by adding the __init__ method to the Student class. For this reason, the __init__ method is usually also called the initialization method.

Let’s slightly modify the Student class above to add two attributes, name (name) and age (age), to student objects.

class Student:

"""Student"""

def __init__(self, name, age):

"""Initialization method"""

self.name = name

self.age = age

def study(self, course_name):

"""Study"""

print(f'{self.name} is studying {course_name}.')

def play(self):

"""Play"""

print(f'{self.name} is playing games.')Modify the code for creating objects and sending messages to objects, and execute it again to see what changes in the program’s execution results.

# Call Student class constructor to create objects and pass initialization parameters

stu1 = Student('Luo Hao', 44)

stu2 = Student('Wang Dachui', 25)

stu1.study('Python Programming') # Luo Hao is studying Python Programming.

stu2.play() # Wang Dachui is playing games.Pillars of Object-Oriented Programming

Object-oriented programming has three pillars, which are the three words we circled for everyone when we highlighted key points earlier: encapsulation, inheritance, and polymorphism. The latter two concepts will be explained in detail in the next lesson. Here we’ll first talk about what encapsulation is. My own understanding of encapsulation is: hide all implementation details that can be hidden, only exposing simple calling interfaces to the outside world. The object methods we define in classes are actually a form of encapsulation. This encapsulation allows us, after creating objects, to only need to send a message to the object to execute the code in the method. That is to say, we complete the use of the method knowing only the method’s name and parameters (the method’s external view), without knowing the method’s internal implementation details (the method’s internal view).

Let me give an example. Suppose we want to control a robot to help us pour a glass of water. If we don’t use object-oriented programming and don’t do any encapsulation, we would need to send a series of instructions to this robot, such as stand up, turn left, walk forward 5 steps, pick up the water glass in front, turn around, walk forward 10 steps, bend down, put down the water glass, press the water dispense button, wait 10 seconds, release the water dispense button, pick up the water glass, turn right, walk forward 5 steps, put down the water glass, etc., to complete this simple operation. Just thinking about it feels troublesome. According to object-oriented programming thinking, we can encapsulate the water-pouring operation into a method of the robot. When we need the robot to help us pour water, we only need to send a water-pouring message to the robot object. Isn’t this better?

In many scenarios, object-oriented programming is actually a three-step process. The first step is to define classes, the second step is to create objects, and the third step is to send messages to objects. Of course, sometimes we don’t need the first step because the class we want to use may already exist. As we said before, Python’s built-in list, set, and dict are actually classes. If we want to create list, set, or dictionary objects, we don’t need to define classes ourselves. Of course, some classes are not directly provided in Python’s standard library; they may come from third-party code. How to install and use third-party code will be discussed in subsequent lessons. In some special scenarios, we’ll use objects called “built-in objects”. So-called “built-in objects” means that the first and second steps of the three-step process above are not needed because the class already exists and the object has already been created. We can directly send messages to the object, which is what we often call “out-of-the-box”.

Object-Oriented Case Studies

Example 1: Clock

Requirement: Define a class to describe a digital clock, providing functions for ticking and displaying time.

import time

# Define clock class

class Clock:

"""Digital clock"""

def __init__(self, hour=0, minute=0, second=0):

"""Initialization method

:param hour: hour

:param minute: minute

:param second: second

"""

self.hour = hour

self.min = minute

self.sec = second

def run(self):

"""Tick"""

self.sec += 1

if self.sec == 60:

self.sec = 0

self.min += 1

if self.min == 60:

self.min = 0

self.hour += 1

if self.hour == 24:

self.hour = 0

def show(self):

"""Display time"""

return f'{self.hour:0>2d}:{self.min:0>2d}:{self.sec:0>2d}'

# Create clock object

clock = Clock(23, 59, 58)

while True:

# Send message to clock object to read time

print(clock.show())

# Sleep for 1 second

time.sleep(1)

# Send message to clock object to make it tick

clock.run()Example 2: Point on a Plane

Requirement: Define a class to describe a point on a plane, providing a method to calculate the distance to another point.

class Point:

"""Point on a plane"""

def __init__(self, x=0, y=0):

"""Initialization method

:param x: x-coordinate

:param y: y-coordinate

"""

self.x, self.y = x, y

def distance_to(self, other):

"""Calculate distance to another point

:param other: another point

"""

dx = self.x - other.x

dy = self.y - other.y

return (dx * dx + dy * dy) ** 0.5

def __str__(self):

return f'({self.x}, {self.y})'

p1 = Point(3, 5)

p2 = Point(6, 9)

print(p1) # Call object's __str__ magic method

print(p2)

print(p1.distance_to(p2))Summary

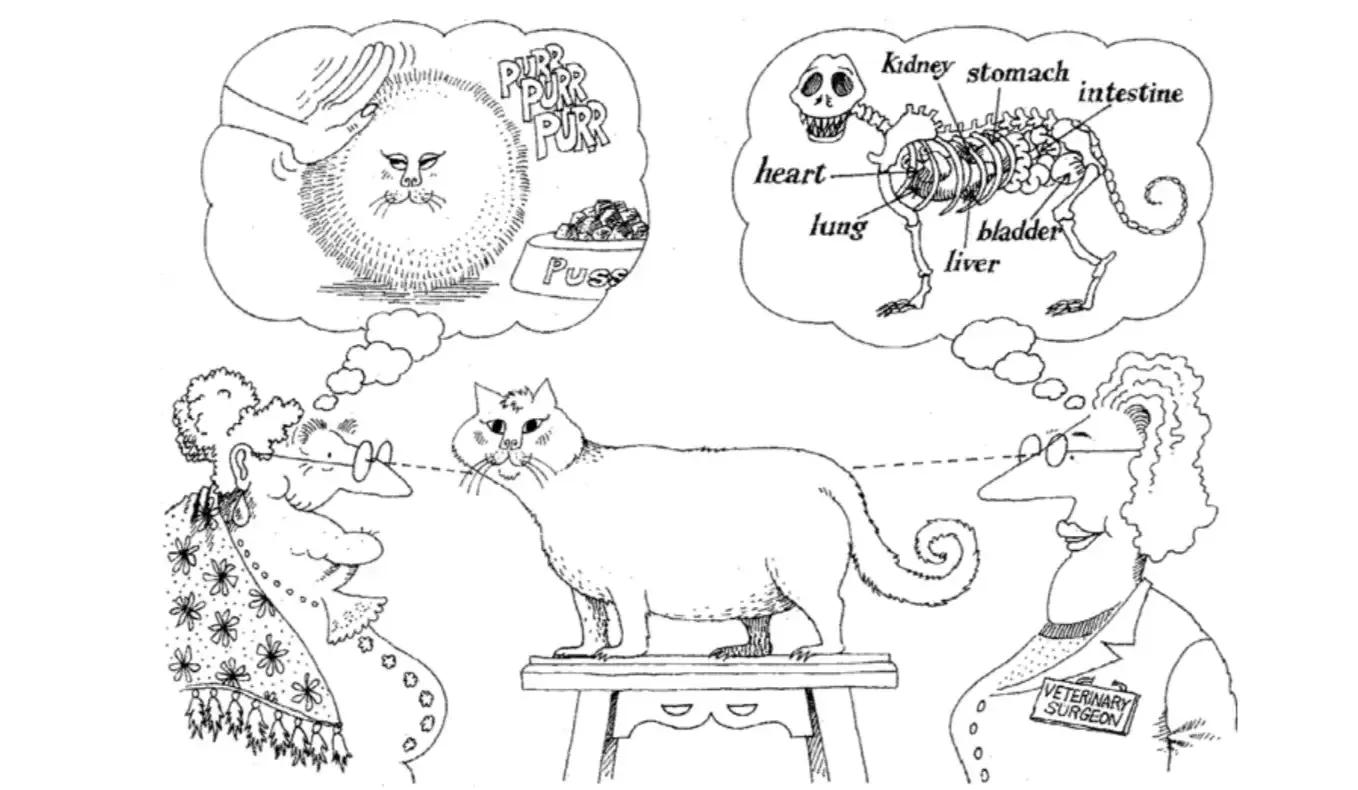

Object-oriented programming is a very popular programming paradigm. In addition to this, there are also imperative programming, functional programming, and other programming paradigms. Since the real world is composed of objects, and objects are entities that can receive messages, object-oriented programming is more in line with human normal thinking habits. Classes are abstract, objects are concrete. With classes, we can create objects, and with objects, we can receive messages. This is the foundation of object-oriented programming. The process of defining classes is an abstraction process. Finding common attributes of objects is data abstraction, and finding common methods of objects is behavioral abstraction. The abstraction process is one where different people may have different opinions. Abstracting the same type of objects may yield different results, as shown in the figure below.

Note: The illustrations in this lesson are from the book “Object-Oriented Analysis and Design” written by Grady Booch and others. This book is a classic work on object-oriented programming. Interested readers can purchase and read this book to learn more about object-oriented related knowledge.